Our last full day in Lisbon was a great end to our trip. We went to the National Tile Museum, took a long walk and went to a cooking class for dinner.

However, I’m splitting up our last day into two posts, so I can dedicate a lot of space to the tile museum. This is definitely something I want to remember. Most of my information here comes from the museum itself.

The museum is located in a former convent – Convento de Madre de Deus, founded in 1509 by Queen Leonor, the wife of King Joao II and sister of King Manuel I. It was the cloistered convent for the Order of Saint Clare (aka, the Poor Clares). It lasted nearly 400 years.

It was dissolved in 1871 (per the museum; 1869 is listed on another website) after the death of the last nun. A hundred years later, its doors opened again as the home of the National Tile Museum because of its unique collection of Portuguese tiles, or azulejos.

First, I’ll cover the convent buildings, then the tiles.

Little remains of the original convent. The current main cloister is the entrance to the museum exhibits, and that was added in the 1550s. It forms an enclosed square with arches and buttresses on each side and a central fountain.

As a powerful, educated woman, Queen Leonor was able to collect some of the best Portuguese and Flemish paintings, sculptures and ceramics of the time. This painting is called “A View of Jerusalem,” and is probably from Germany. Historians believe Emperor Maximilian gave it to his cousin, Queen Leonor.

It is a highly detailed progression of the Passion of the Christ. It is behind thick, protective glass, and reflections on the glass make it difficult to get good photos. Here are some close-ups, with my guess as to what they show:

The lower choir room of the original church was once the main choir room at the time of Queen Leonor.

Fancy, eh? Over time, that room was frequently flooded, so the lower choir room was then used as a mortuary, and the altars in that room relate to death. Click an image to expand the photo gallery:

Choir friends, if you think that looks fancy, just wait. Here is the upper choir room:

The upper choir room was where nuns were allowed to worship.

The sanctuary itself is embellished with tiles, art and gilding. The lavish decoration started to be added by King Joao III in the 1550s. Somehow, this doesn’t quite jive with a place that was a convent for the Poor Clares.

The blue and white tiles are Flemish and were added in the 1600s. The paintings are Portuguese and framed in gilded carving, or wood that is covered in a very thin layer of gold. According to the museum, the gold is so thinly layered that six gold coins would have been sufficient to decorate the entire space. Will and I are skeptical.

Here is a closeup of the archway:

To get from the lower choir to the worship space, visitors today have to climb some stairs. Those were added in the 19th century. When this was still a convent, the nuns were not allow to enter the church, so those stairs weren’t needed until later. Harumph.

On the second level of the church is a room with a giant nativity scene:

This is the oldest baroque nativity scene in Portugal. After the convent’s last nun died, many items were boxed up and stored away, including this nativity. It wasn’t discovered until the early 2000s and went on public display in 2006.

I noticed an unusual figure in the scene, this woman with a rooster:

Supposedly she is from a 15th century folktale called The Legend of the Rooster of Barcelos. A man who was wrongly convicted of a crime said the judge’s roasted rooster would crow again when the innocent man was executed. Sure enough, as the man was about to be hanged, the dead rooster crowed. The man was saved at the last minute by a faulty knot and the judge’s change of heart. The Rooster of Barcelos is a symbol of faith, justice and good luck.

Moving on to a different part of the convent, the “cloistrim” is a small cloister up two flights of stairs and existed during Queen Leonor’s time.

At the back is the the Santa Auta fountain, believed to have miraculous powers.

Though the tiles around the cloistrim are stunning, they were not added until the 1800s from another convent that was being demolished.

The stairway leading to the cloistrim is decorated with tiles. When we were there, I saw two people working in this stairwell and wondered if they were restoring tiles.

Alas, no. This is what they were adding:

Ha ha! Joke’s on me.

As you can tell, over the centuries since the first convent was built, this convent became a repository of tiles from around Portugal and other convents. During the 20th century, that helped cement the convent as the future home of the National Tile Museum.

Now on to the tiles.

The Portuguese word “azulejo” comes from the Arabic word “al-zulaich,” meaning polished stone. As Will noted in his Facebook post, tiles were brought to the Iberian peninsula from Northern Africa by the Moors.

Will: I really like this original Arabic style.

When the Moors took over the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century, they used azulejos to simulate large tapestries. The first tiles were imported from Spain. One of the benefits of using tiles on walls is their reflective properties. In a time without electricity, candlelight would reflect off the tiles.

Because Portugal did not have many natural colorful stones, a new technique was created by making azulejos from baked clay that was then painted with metal oxides and reheated. The different oxides created different colors.

The baked clay was broken into small shapes and reassembled into designs. I can’t help but equate this to how quilts are made!!!

After the Iberian Peninsula was taken over by Christians, Portugal (unlike Spain) was still a livable place for Jewish and Muslim populations. Alas, Spain’s Inquisition later spread to Portugal. But for a while, Muslim tile artists continued to work in Portugal. This star motif was a common one they used.

By the late 1500s, the majolica style emerged, which is very similar to today’s modern tile techniques. It uses glazed earthenware that was then painted.

Will: When the Moors were expelled, tile art was commissioned by the Church mostly, which allowed depictions of animals and humans, but mostly religious works for churches and convents.

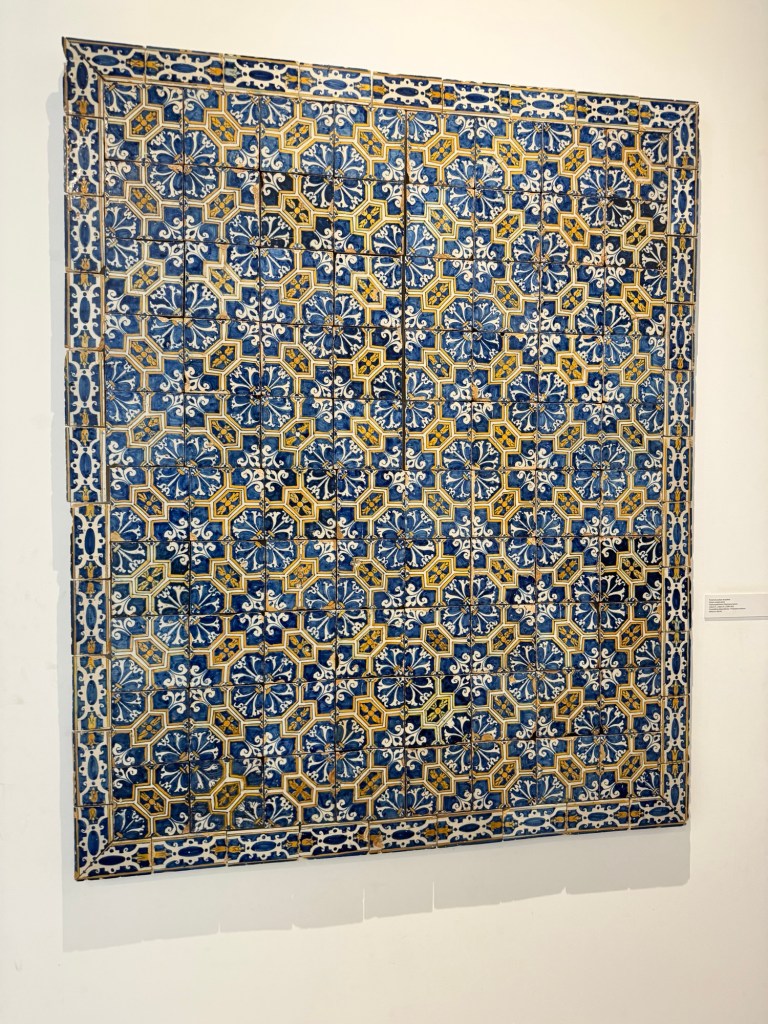

The artwork below, created in 1580 for a church in Lisbon, uses that majolica style and is considered to be one of Portugal’s azulejos masterpieces. It has a precision and range of colors not seen in many pieces from the same time. That church collapsed in Lisbon’s 1755 earthquake, but this piece was saved.

One religious artwork put me in mind of our canine family members:

Some of you may know (unlike me) that St. Dominic’s mother had a dream when she was pregnant with him. In the dream, a dog leapt from her womb with a torch in its mouth. This was interpreted to mean her child would set the word on fire. St. Dominic is often painted with a dog that is holding a torch. (At first, I thought this was just a cute dog rendering. Now I know better.)

The stairway panel below, made around 1630 in Lisbon, is unique because the azulejos were cut into diamond shapes to fit a sloping stairway. This panel was originally in a convent that is now Portugal’s Parliament Building.

Dutch tiles began arriving in Portugal in the late 1600s. Their style of blue on white scenes heavily influenced the Portuguese tile culture.

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake also influenced Portuguese tile making. The Marques de Pombal, essentially the prime minister of the time, quickly rebuilt the city using tile work on all the streets, sidewalks and building exteriors. Because of this high demand for tile, production became more industrialized. You’ve seen this civic tile work in our previous posts as well.

Tile work known as “Pombaline” can be seen a lot in my next post on our walk through the city. This example is in the museum:

Fast forward to the 20th century. Will and I both liked the modern art influences on Portuguese tile.

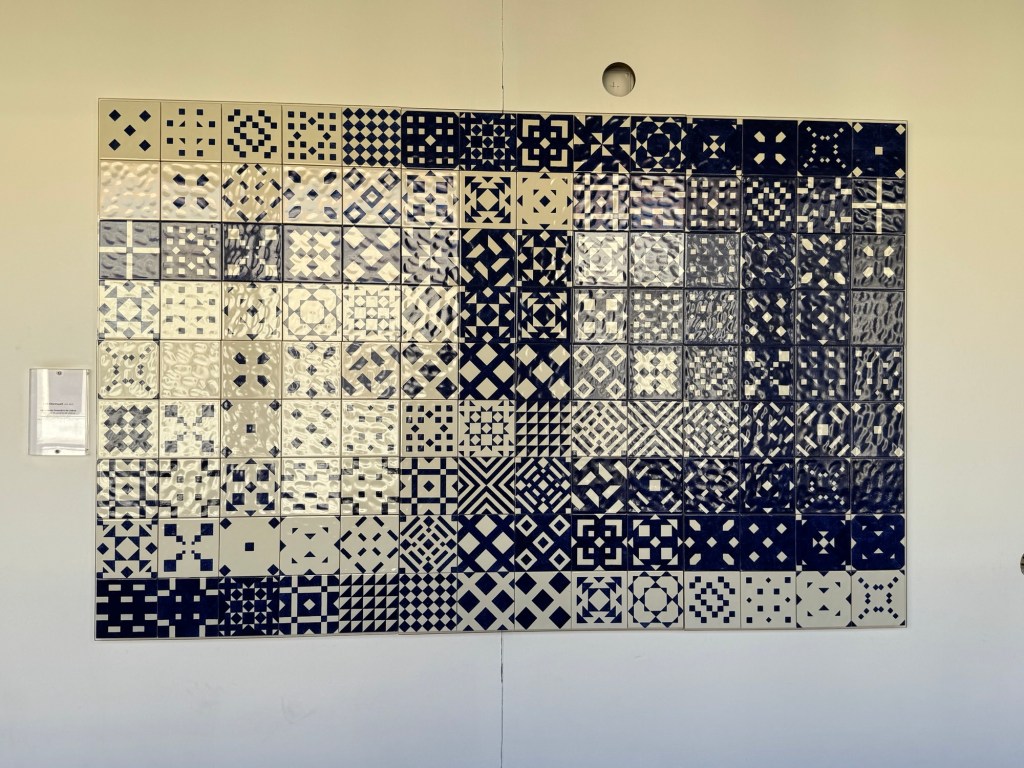

The entrance area with the ticket booth, cafe and gift shop has this incredible artwork:

The artist was Querubim Lapa, a 20th century Portuguese tile artist. He created two of these, and the other one hangs in the Portuguese embassy in Brazil.

So that’s it for the tile museum! After leaving here we took a taxi to the Praca de Commercio. Our walk through the Baixa district will kick off part II of our last full day in Lisbon!

Leave a comment